WASHINGTON—Clarence Paul Ratliff was sitting in the cockpit of his Grumann F6F Hellcat on the flight deck of the U.S.S. Aircraft Carrier Saratoga (CV-3) at 1700 hours (5 p.m. local time), Feb. 21, 1945, when he heard someone tapping on the side of the aircraft.

Adrenalin flowing and already a veteran of the European Theater of Operations after having supported the invasion of Southern France, the 22-year-old Oklahoman was as primed for action as was his fighter plane sitting atop a catapult in “Ready One” status in case he was needed to help provide air support for the Marines fighting on the nearby Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima.

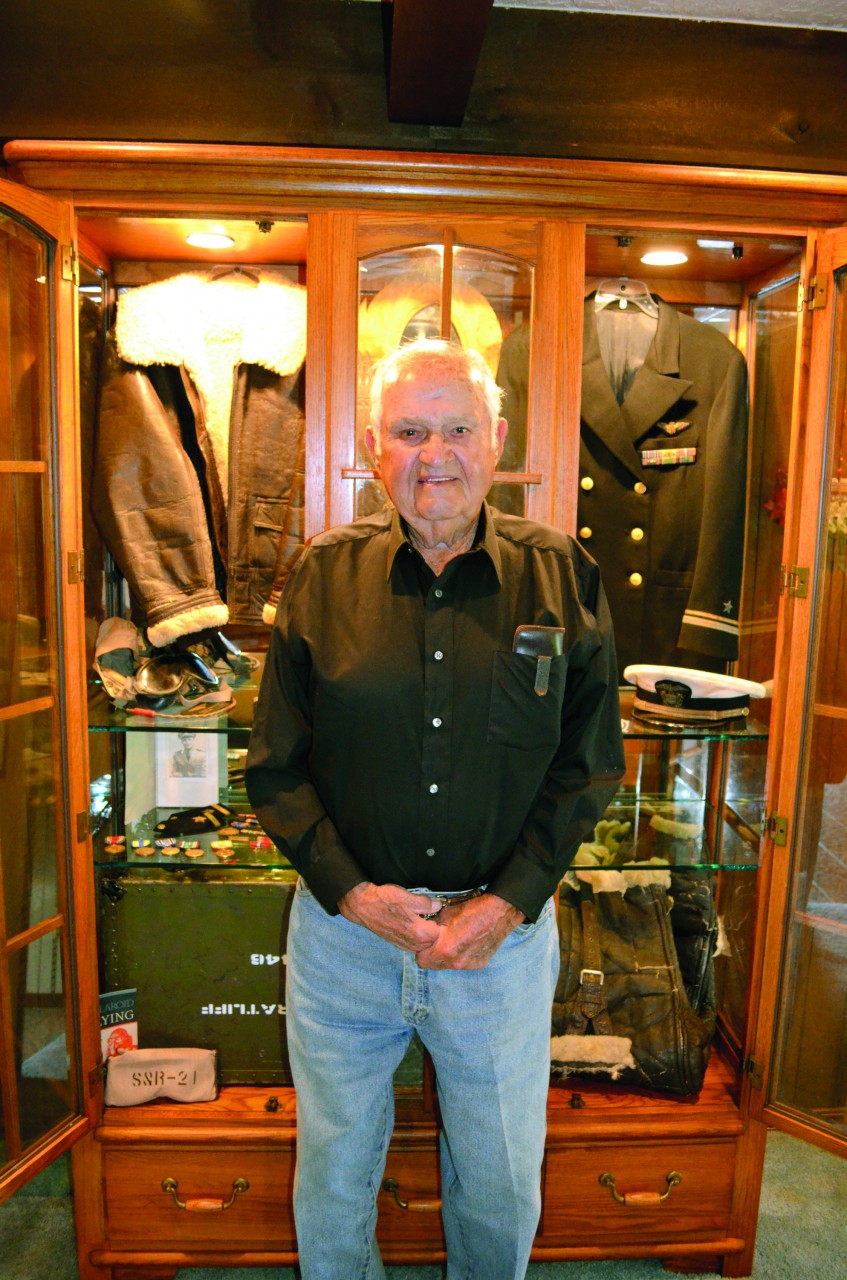

Paul Ratliff in front of the display case his son, Paul Dewayne, provided for his World War II memorabilia.

Ratliff, now 92, and a longtime member of Washington, First, recalled what happened next in the book, My Father, My Friends—Memories of World War II by Sparky Barnes Sargent.

“Someone I didn’t recognize knocked on the side of my Hellcat and told me, ‘I’m a night fighter, and I’m taking your place now.’ I got out of the catapult and went down the ladder at the 5-inch gun mount—and right then General Quarters was called and the Japanese started firing. About that same time, the airplane sitting on that catapult was taken out by a kamikaze pilot.”

Sitting recently at the dining table in the home he and his late wife, Juanita, built in 1975 on her family’s Indian allotment homestead, this soft-spoken, modest, unassuming American hero—although he is uncomfortable with anyone using that term to describe him—credits Jesus Christ for everything in his life.

“I got out of that airplane and I hadn’t walked very far, and my airplane was gone,” he said quietly, his eyes misting. “A kamikaze pilot had hit it. In the next day or two, a Chief Petty Officer and I dug the Japanese pilot out of the lower decks and I still have a part of his diary somewhere.”

According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, there are about 1.8 million of the 16.1 million World War II veterans still living, with an estimated 850 dying every day.

Ratliff, a Choctaw, enlisted in the U.S. Navy on Aug. 28, 1942 as a 20-year-old who was 5-8 and weighed 135 pounds. He left the service almost exactly four years later. Sargent’s book lists him as having earned several decorations, including the Air Medal with three Gold Stars; the Bronze Star with a “V,” American Campaign; European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign with one star; Asiatic-Pacific Campaign with three stars; Liberation of the Philippines; Expeditions (For U.S. Navy Service) and the World War II Victory Medal. He had flown the Boeing Stearman N2S, Vultee SNV Valiant, North American SNJ, Vought F4U-1 Corsair and Hellcat aircraft while participating in the Invasions of Southern France, Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

As such, he fit perfectly the definition of a member of the “Greatest Generation” as specified by Tom Brokaw in the book by the same name:

“They answered the call to save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs. They faced great odds and a late start, but they did not protest. They succeeded on every front . . . As they now reach the twilight of their adventurous and productive lives, they remain, for the most part, exceptionally modest . . . In a deep sense they didn’t think that what they were doing was that special, because everyone else was doing it too.”

— Tom Brokaw, The Greatest Generation.

Ratliff, who still helps run the 200-acre 3R Bar Ranch—a Limousin cattle operation designated an Oklahoma Centennial Ranch—with his son, Paul Dewayne Ratliff, an agent for Travelers Insurance and also the Mayor of Washington, said he “loved” the Navy. But, he loved and respected his wife, Juanita, even more.

“I loved everything about the Navy. In fact, I wanted to stay in the Navy after the war,” he asserted. “And, when the war was over, they were going to transfer me to Hawaii. But, Juanita and me at that time had one child and she said, ‘Hon, it’s just too far from mama.’ See, she had stayed with her mama all during the war while I was gone, and I had to respect her wishes.”

So, back to McClain County they came.

But, flying was still in his blood, so Ratliff joined the Naval Reserve and drove to Dallas every other weekend and flew his beloved Hellcats. He remained in the Reserves “for quite a few years,” he said. Ratliff later had a 26-year career with Aero Commander/Rockwell in Oklahoma City.

Ratliff’s roots are planted deep in the rich soil around Washington. Both his maternal grandfather, Archibald Stonewall Jackson Barnett, and his father, James Alexander Ratliff, were preachers. In fact, his father served as pastor of Washington, First from 1923-29, being paid the princely sum of $7— a month! Barnett also pastored Barnett Prairie Church, and he and his wife, Elizabeth, had 17 children.

Ratliff said he was saved during a brush arbor revival his father preached in Bridge Creek, and he was baptized at Woody Chapel south of Washington just before he went into the Navy.

Looking back on his nine decades, he said, “My life didn’t just happen. God has been walking with me through it. I’m just an old country boy, but I know the good Lord was with me all the way, or I wouldn’t be here today.”

Now in his twilight years, Ratliff enjoys life with his family, which now includes one son and three daughters, 10 grandchildren (seven granddaughters and three grandsons), 15 great-grandchildren (10 great-granddaughters and five great-grandsons), and two great-great-granddaughters.

Of course, having a big family is nothing new for a man who came from a family of 12 children, and had six brothers and five sisters.

“I wouldn’t take anything for how close I am to the Lord,” he commented. “He has been with me ever since I have been a Christian. I wouldn’t have made it through the Navy if it wasn’t for Him.

“I could give you many examples.”

And, then he launched into one.

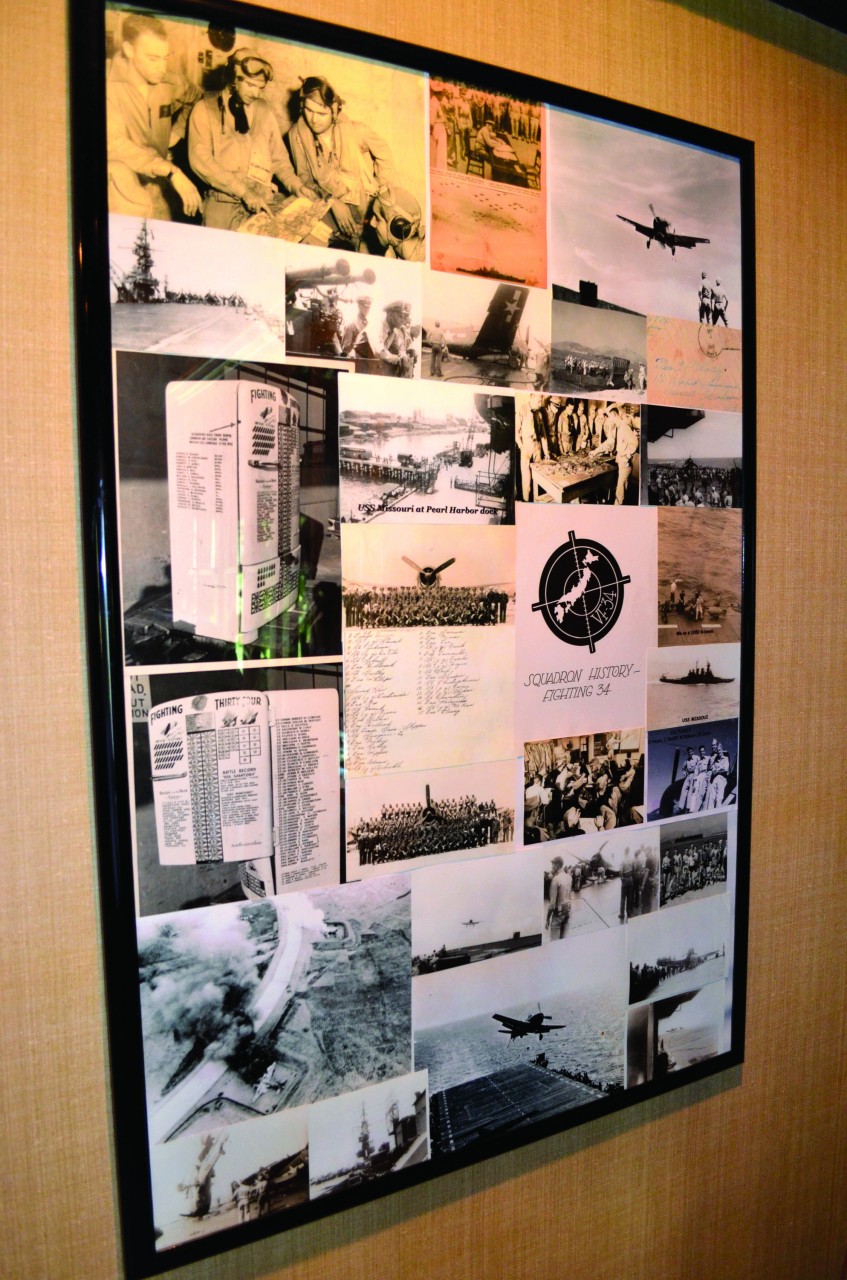

Photos of Ratliff’s wartime exploits are displayed in a large frame in his den.

“I had finished all of my flight training in Pensacola, Fla., and all I lacked was my instrument flying. It was so difficult for me. I could fly the airplane, no problem, but when they closed the hood and I had to concentrate on just those instruments to fly, that was difficult. After a flight, my instructor told me, ‘tomorrow, you’re washed out,’ because he knew I had to pass my instrument flying test the next day.

“Well, I went out to the airplane early the next morning and I took the old, worn New Testament my daddy had given me, and I prayed and turned to Philippians and read 4:13, ‘I can do all things through Christ, Who strengthens me.’

“We took off and got to the starting point to where you were to fly a square course only using the instruments and get back to the starting point, and I did it! My instructor was astonished. He just knew I couldn’t do it.

“Would you believe I never had a problem flying instruments after that! That’s just one time the Lord helped me.”

Members of Washington, First honored their World War II veterans this year just prior to Independence Day. Ratliff just happened to be the only honoree who showed up—because he is the ONLY such veteran who attends the church.

Interim Pastor Rob Miller said he felt it was the right time to honor Ratliff.

“We had decided that Independence Day would be a good time to recognize him, and make a big day for him being the only World War II veteran in the church,” Miller said. “He didn’t know that was going to happen until we presented the certificate to him, so he was pleasantly surprised.

“But, a number of the people in the church on that day were only made aware then that he is a World War II veteran, because he is so low key about it. He is so non-assuming about who he is that I would say that probably the majority of the people found out that day that he was a World War II vet, and it was amazing after the service was over to see the number of people who lined up to shake his hand and thank him for his service to his country.”

Ratliff’s son, who did not serve in the military, but whose son, Paul Ryan, now serves with the U.S. Marines, and was deployed twice to Iraq and twice to Afghanistan, is justifiably proud of his father’s service to his country.

“I talk to the young kids at our family reunions, which often include as many as 130 people. I point dad out, and say, ‘Look at that 92-year-old man. Can you imagine him in the cockpit of a fighter plane flying off the decks of aircraft carriers, engaging in dogfights and dropping bombs?’ And they say ‘No.’ And then, I ask them, ‘Can you see yourself doing it right now at 20-21 years of age?’ And they just shake their heads and say, ‘No.’

“And I tell them, ‘That’s what he did at your age. It’s Incredible!’”