Joe Williams and his wife, Linda, survey the names of more than 600 bombing survivors etched into salvaged pieces of granite from the building’s lobby hung on the Survivor Wall, which adorns the last remaining section of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building (Photo: Bob Nigh)

Joe Williams is familiar to his innermost being with the terms Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Compassion Fatigue. You could almost say he wrote the book on them, or at least edited it.

But, he had to deal with the terrible images of death and destruction on a deeply, intimately personal level before he could begin to help others deal with the images and issues that plagued them after tragedies such as the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995.

Williams, 79, recently poured over more than 100 photographs he had saved since that terrible spring day in the Sooner State’s Capital and donated most, if not all, of them to the Oklahoma City National Memorial as the 20th anniversary of the bombing approached.

“Doing that brought back a lot of memories,” he sighed, reflecting on an event, which he said, “Changed my life.”

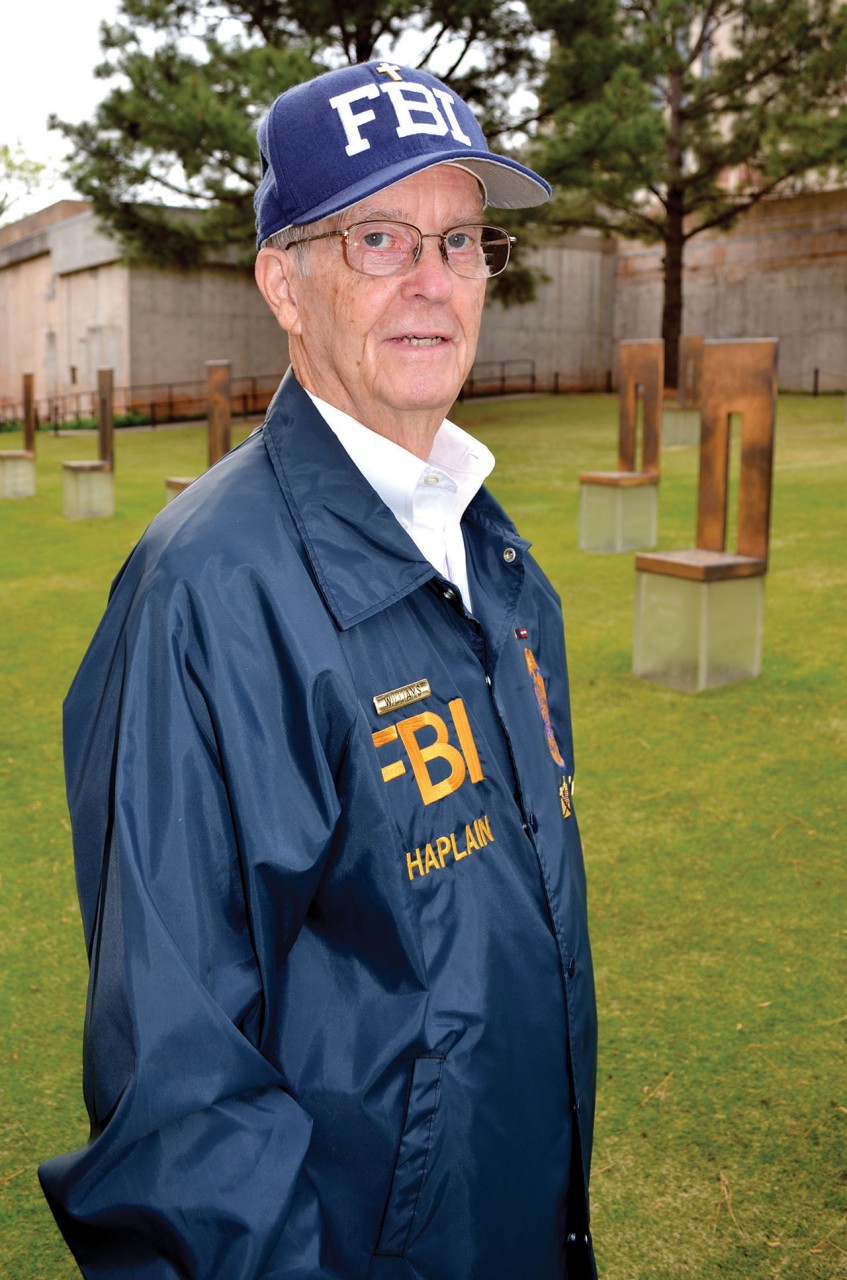

Williams, who was the chaplaincy and community services specialist with the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma (BGCO) and a chaplain with the FBI at the time of the attack by Timothy McVeigh and co-conspirator Terry Nichols, said he spent almost three weeks at the site following April 19.

“I spent probably 12-15 hours a day down there,” he said. “Jack (Oklahoma City Police chaplain Jack Poe) and I were scheduled to be in Boston for some more training that week, but I told him I was so full of that training that I didn’t think I’d go and he said, “If you’re not going, I don’t think I’ll go, either.’

“Had we been gone, we wouldn’t have been here that day.

“He and I both had taken some seminars on PTSD, though we’d not experienced it until after the bombing. A lot of the training we had received addressed that issue quite a lot.”

It wouldn’t be long until Williams faced what causes PTSD personally.

Williams looks through articles about the bombing in file copies of the Baptist Messenger from 1995 (Photo: Bob Nigh)

“I can remember one of the days after (The bombing) I had been down to the Medical Examiner’s office, and in one of their refrigerated rooms, they just had little arms and legs laid out trying to figure out how many children they actually lost, and I needed to see that, so I would know what they were working with,” he explained. “The next morning, my granddaughter—she was about three—I saw her running down the hallway away from me in our house, and I saw her blown apart.

“After that, when I saw children, that’s the way I would see them. So, all that stuff is coming back. We later took out that hallway in our house and made the den bigger to help get rid of that image.”

But before the home remodeling, FBI supervisors in Quantico noticed changes in Williams as they read his daily reports, and took measures to get him help.

“I got a call from my secretary about 20 days after the bombing, and she told me the FBI chaplain coordinator said my airline tickets were ready for Washington, D.C.,” Williams said. “I told her I wasn’t going to Washington, but she insisted they wanted me to come.

“I called to see what was going on, and he told me they needed me to come and meet with other chaplains to discuss what would be needed to be done in the future because they expected similar incidents in the future.

“So, I went, and these two guys in dark suits met me at the airport. I found out later that they had checked with my secretary and my wife at the time, Dorothy, to check on me. They also had read my reports and were worried about how I was doing.

“They took me to a hotel, and, pretty soon, I met with someone to go over some of the things in my reports. Later, a police psychologist from Boston came in and said the other meeting really would be held later, but he asked me to go over all of my experiences, and I unloaded my garbage on him over three hours, especially the incident with the children and my granddaughter.

Williams in his FBI chaplain jacket and cap stands among the Field of Empty Chairs, which memorializes those who perished. (Photo: Bob Nigh)

“We went through the process of EMDR—Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing—where you take an image that’s in your face all the time mentally and you shift it; you move it to where you can recall it if you want to, but it’s not right in front of you all the time.

“On the way downstairs, I was in a hurry to see some children to see how well he had done his job. Sure enough, we saw some children, and he stood back and held his breath. He watched as I looked at them.

“After a few minutes, I turned back to him with tears in my eyes and said quietly, “They stayed together.”

Williams became an FBI chaplain on Jan. 1 1991 when the FBI began its national program, selecting one chaplain from each state to join the program.

“I was a member of the team that was still putting together the program in 1995,” he said.

Williams began as a chaplain with the Nicoma Park Police Department in 1982 when he was pastor at Nicoma Park, First.

In response to the bombing, he worked with the BGCO and FBI personnel, and Poe worked with the OCPD, the Secret Service and the National Guard.

“None of the other federal agencies had chaplains,” Williams said. “We made some death notifications for some of those.”

The bombing was personal to him, of course, in that he had to make death notifications to families of members in his church who were killed in the blast.

“One of the difficult duties I had was to make those death notifications,” he commented.

Williams said one of the most frustrating aspects of the bombing response was coordinating chaplaincy overall.

“One of the things that Jack and I did, along with Jack’s wife, Phyllis, that others would not have been able to do quite as well, was that we had an influx of people coming in who wanted to be chaplains and tried to convince us they were chaplains. Well, everyone had to go down to the command center to get credentials to get inside the perimeter.

“Some of them were getting credentials to get inside just to take pictures of bodies, or pick up pieces of evidence and put them in their pockets. We had about 250 chaplains eventually.”

Not only did Williams minister as a chaplain, but he also represented the BGCO as a member of the committee that distributed donated funds after the bombing to survivors and victims’ families. The total was more than $400,000.

Since that fateful day in April 1995, Williams has held Psalm 139 close to his heart.

“I would have to say the Scripture that comes to mind that has meant so much to me is Psalm 139. Because it talks about the fact that God has always known us; He always knows where we are; He always knows where we will be, and I have been able to say, ‘Lord, I don’t need these thoughts, and I want You to take them so I can sleep,’” he said. “But, I never got the peace of Him doing that until I said, ‘And, I want to thank You for taking them, and thank You for the sleep you have given me.’ That’s worked for me.”

He continued to get training after the bombing—including working on compassion fatigue with Charles Figley at Florida State University—and eventually formed the Crisis Intervention Institute, which conducted seminars and training on traumatology, compassion fatigue, disaster preparedness and response to violence.

“We did three-day workshops for eight-and-a-half years, once a month in Stillwater for victim families, survivors and first responders,” he said. “I started doing seminars on compassion fatigue for different groups—law enforcement, fire fighters and medical personnel. Then we modified it to fit what we wanted to do. I have one for pastors, and we changed the name of it to Maintaining Resiliency and Effectiveness in Ministry. Depending on what group it’s for, we change the last word to match the group.

Despite all the tragedies that came out of April 19, 1995, Williams loves to recount one victory.

“A law enforcement officer came to one of my workshops for family members, first responders and survivors,” he related. “They were told not to wear their uniforms, but he came in with his on, anyway. He wasn’t happy about being there. He came in, and I tried to shake his hand and introduce myself, and he snapped, “Get out of my way, old man, I don’t like you, I don’t want to be here, just stay away from me.”

“There were about 18 people there. During introductions going around the circle, he said, ‘I only like one of you people, and he’s an Oklahoma City police officer and he writes tickets like me.’

“The first night, I told him we had a room for him and he said, ‘Old man, I told you I don’t like you. Stay away from me,’ and he left.

“I didn’t think he’d come back, but he did.

“The third day, we were getting ready to close out and he said, ‘Old man, stand up.’ He walked over and put his arms around me and hugged me. Then he backed up and said, ‘You saved my marriage, you saved my job, you saved my life,’ as he patted his holster holding his service revolver.

“When I was in New York City later in 2001 after 9-11, I had him come out several times, and we worked a lot with first responders. He was so fantastic with first responders because he had been there.”

Williams has been asked to speak at a church on the 20th anniversary of the bombing, and said he will probably do so. He also plans to attend a reunion of first responders on Sat., April 18.

“I still have flashbacks,” he admitted. “I go back to where that building used to stand, marvel at the survivor tree and the reflecting pool, and walk through the field of memorial chairs, and the memories come flooding back. But, God has given me a sense of peace about everything.”