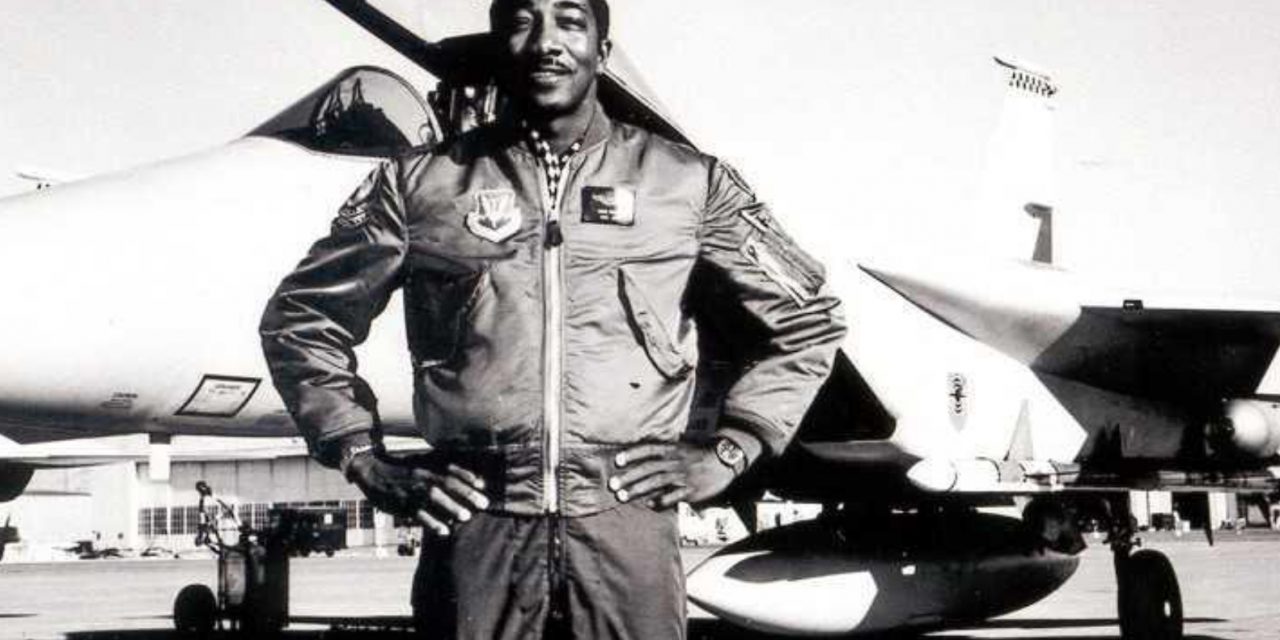

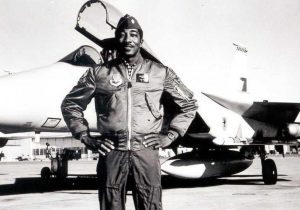

Southern Baptist “Top Gun” Richard Toliver found freedom in the cockpit, from which he had dodged missiles and anti-aircraft fire while flying 446 combat missions in Southeast Asia during his twenty-six-year Air Force career.

He also battled racism.

Toliver’s idyllic childhood was spent in multi-racial California—“paradise,” as he remembers it—during the early 1940s. He dreamed of flying airplanes like those that flew overhead from nearby Oxnard Naval Training Base. That dream shattered when his family returned to his segregated birthplace in the South after wartime jobs ended.

“I hated the next 10 years living in the South,” Toliver told SBC Life. “I was trapped in a prison. Everywhere there were barriers of poverty, color, hopelessness, despair and vicious name-calling.”

Today, Toliver at 82 years old has held key positions at Glendale, Ariz. Apollo. He also is president of the local chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen, active in the Red River Valley Fighter Pilots Association, and a nationally-known motivational speaker.

In his nearly 500-page memoir—An Uncaged Eagle: True Freedom—Toliver gives credit to the many people who encouraged him throughout his life. He writes of his courageous mother, family relatives, and a white man who was a “ray of light” in the darkness of racism.

That man provided Toliver, a Black high school graduate, with a scholarship to study at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, now University. There he met and learned from the Tuskegee Airmen who broke the military’s color barrier in World War II, who “inspired, motivated, and prepared” Toliver for an Air Force career, he said. Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., fellow Air Force officers, and in the 1990s, presidential candidate Ross Perot were others who impacted Toliver’s life.

More than anyone else apart from God, Toliver credits his wife Peggy’s Christian life for his success. Married 58 years, she dazzled Toliver and the Air Force community with her gracious attitude, warmth and servant’s attitude while successfully parenting the family’s three biological and five fostered or adopted children.

Toliver’s disciplined character and Peggy’s background as an educator and stalwart Christian kept their children on the right path, the retired colonel said. They were also aided by Peggy’s mom, Elsie Hairston, who lived with the Tolivers for 27 years after his father-in-law died.

“The most important part of my life’s experience was discovering that God is in control of everything,” Toliver said. “He allowed me to become all that I am today.”

After years of putting God off and making “deals” he failed to keep, Toliver had what he calls a “Damascus Road” experience at high altitude in clear air. The F-15 he was piloting was struck by lightning.

After safely landing the crippled jet, Toliver heard a voice that said, “How long are you going to keep up this charade? How long are you going to refuse to settle your debt with me?”

Toliver wrestled with those questions over the next few days. “Even the family dog avoided me!” he said.

He found himself spiritually and mentally on trial. There was a “Prosecutor,” who listed even his sins from childhood and declared him “guilty.” However, an abiding “Presence” stood in Toliver’s defense, and “the hand of Jesus reached down and grasped my outstretched hands,” Toliver writes of his gripping salvation experience in his book.

Toliver, the first fully qualified African American F-15 pilot and successful in hundreds of combat missions, once acquired the nickname “Black Baron.” This was in deference to the acclaimed German “Red Baron” of WWI. After Toliver’s conversion, others started using “Preacher” as his call sign as a recognition of the pilot’s frequent scripture-based remarks and lifestyle void of previous colorful language and behavior.

Working out his salvation took much longer than his initial capitulation to Christ, Toliver said. He had to deal with the incessant anger that burned within him whenever faced with adversity, setbacks and real or perceived racism. “I was committed to allowing the Lord to guide my path, but ‘self’ kept getting in the way,” he said.

Through Bible study and prayer, Toliver eventually came to realize that achieving success in the Air Force had become an idol for him. Ultimately it was in the person-by-person forgiving of people who had wronged him that Toliver first glimpsed true freedom.

He had to forgive his father for leaving his mother with six children to struggle for themselves in the Deep South. Next it was his brother-in-law for his mistreatment of Toliver’s sister.

“Only then did the healing begin for past hurts caused by racial prejudice, slights, disappointments, and other emotional barriers,” Toliver wrote. “I finally found my freedom. The cage of despair had to be opened from the inside, and the path to freedom was through the door of forgiveness.”

After hearing a base chaplain preach that parents needed to allow Jesus Christ to be the perfect model for their children, Toliver called his family together. He told them he was flawed, and they needed to look to Jesus as their example. “A tremendous burden was lifted from my shoulders,” he said after his family reiterated their love for him even though they recognized he was not perfect.

Toliver retired from the Air Force in 1988, four years after being promoted to Colonel. Consulting jobs led to political activism, which in time resulted in being introduced to Ross Perot, the U.S. presidential candidate for the Reform Party in 1996. In Perot’s introduction to Toliver’s book, the billionaire wrote, “Dick spent his formative years overcoming incredible obstacles during some of the most challenging racial times of the Deep South… His personal struggle and eventual freedom serve as a roadmap for anyone who feels trapped by life’s circumstances.”

Toliver’s bottom line: “True freedom… enables us to act selflessly, forgive all injuries, love unconditionally and humbly serve without expectation of rewards. It is the spiritual state that reaches the very presence of our Creator.”