Dr. Benjamin Myers’ 2019 sonnet cycle Black Sunday has been named one of the “Five Best: Stories of the Dust Bowl” by The Wall Street Journal, earning recognition alongside John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.”

The national spotlight came in a June 25 story by novelist Hazel Gaynor, who praised Black Sunday for placing readers “right there, as if we are peering through the window of a homestead on an Oklahoma prairie.”

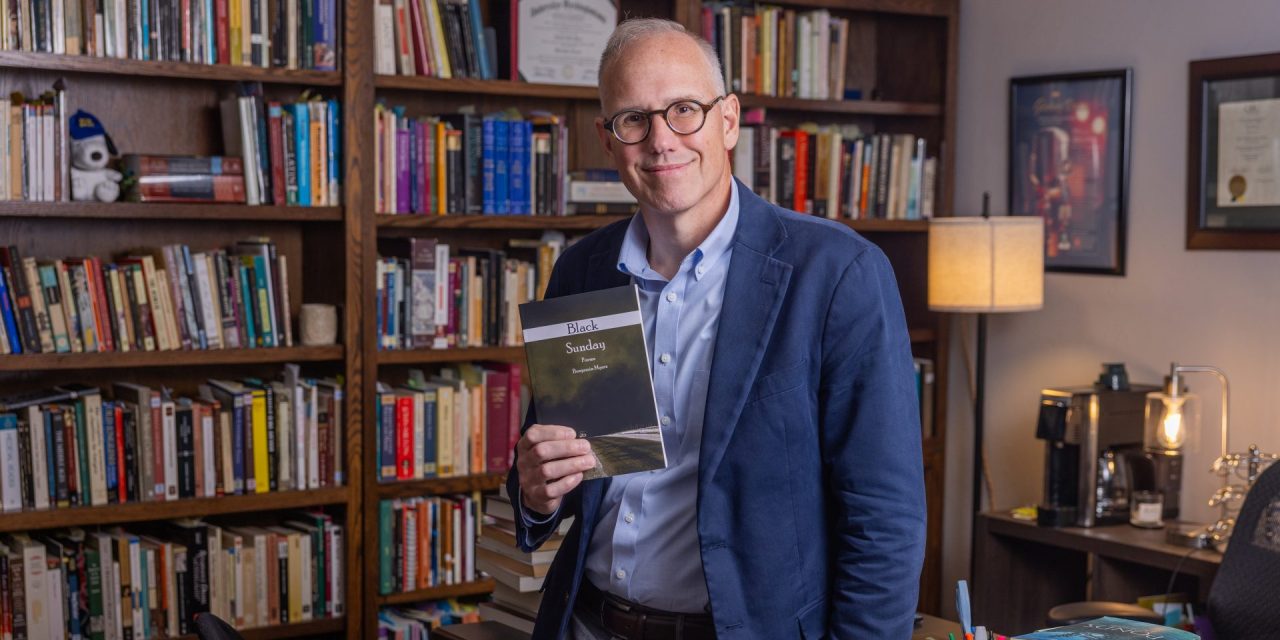

Myers, director of the Oklahoma Baptist University Honors Program and the Crouch-Mathis Professor of Literature, said, “My initial reaction was complete surprise.”

“A friend pointed the article out to me,” said the former Oklahoma Poet Laureate and author of multiple books of poetry and nonfiction. “Otherwise, I would have had no idea.”

The article lauded Black Sunday, a compact collection of persona poems written in sonnet form, for its vivid portrayal of rural life during the Dust Bowl through the imagined voices of a farmer and his wife, their daughter, a teacher, a minister and others.

“His lines are as vivid as photographs,” Gaynor wrote, citing images like “She hacked and coughed so hard it shook her bones like pine trees in high wind.”

“Any artist is happy to receive affirmation that the work is connecting with an audience,” Myers said. “I’m very happy to know that the book has found readers not only in Oklahoma but also nationally. Poetry doesn’t get a lot of press, so praise in the pages of The Wall Street Journal is an unexpected bump in the book’s reach, for which I am very grateful.”

He began writing Black Sunday while serving as Oklahoma’s poet laureate in 2015–2016.

“I reasoned that the Dust Bowl is to Oklahomans something like what the Trojan War was to the Greeks and Romans, so it seemed like a subject I should take up as laureate,” Myers said. “Beyond that, as a Christian poet, I was looking for a way to write about faith, hope, and love, but you can’t write about those things without also addressing suffering and fear.”

He grounded the project in extensive research, including first-hand accounts from the era.

Myers said he felt lucky that his Poet Laureate duties took him to the Panhandle, so that he was able to “spend some time in the landscape.”

The recognition is even more significant considering the company. Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath,” published 80 years before “Black Sunday,” remains one of the most enduring portrayals of the Dust Bowl and its toll on families.

“It is an honor to be in the company of a great American writer like Steinbeck,” Myers said. “His book is probably one of the first things most people think of when they think about the Dust Bowl.”

Myers first encountered Steinbeck’s novel in high school but was already familiar with its cinematic counterpart.

“Before that, I had already seen John Ford’s film version many times, as my family watched it every year when it came on television,” he said. “I think both the book and the movie helped me realize that the stories of my place and my people could be a fit subject for literature and could be compelling to people from many different places and backgrounds. It helped me realize that the stories that happen in Oklahoma are simply particular versions of the universal human story.”

Late in the writing process, Myers reread “The Grapes of Wrath” and also discovered Sonora Babb’s “Whose Names Are Unknown,” another Dust Bowl novel.

“I love Steinbeck’s grand mythic treatment of his subject, but I think that Babb’s novel is the more intimate and humane treatment,” he said. “I tried to land closer to that inside view that Babb gives.”

The recent Wall Street Journal article singled out Myers’s work for making history feel “present.”

For Myers, that phrase carries weight.

“I was very pleased to see that phrase because I believe history is always present,” he said. “As Faulkner famously said, ‘The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.’ Christians, especially, are aware of how the past lingers in the present, because we can observe God working through time when we read Holy Scripture. So much of the Bible is dedicated to history and to poetry.”

Myers said poetry has a particular power to pull the reader into a moment.

“A poet’s job is not to tell the reader about something but rather to put him or her into a particular time and place. When poetry engages with history, it can have a pronounced power to bring the subject to life.”

The formal constraints of poetry, he added, are part of that power.

“I really like the challenge of getting Okie dialect into iambic pentameter,” he said. “But, more than that, I wanted a form associated with intimacy and interiority, since most of the poems are presented as the private thoughts of the characters.”

In Myers’s view, the sonnet form offered the right emotional register.

“The sonnet has a long association with dramatizing the thought process, particularly in relationship to feelings of longing,” Myers said. “Shakespeare’s love sonnets come to mind, but also John Donne’s sonnets about God. That seemed like a good form for exploring what passes through the mind of someone in the midst of trial, someone longing for hope.”

While writing Black Sunday, Myers said, he discovered who the central figure had become.

“The hero of the book, the one carrying the hope for the others, was Lily Burns, the mother and wife,” he said. “I think I based that aspect of her character on observation, having seen many strong women carry the hope and faith for entire families.”

Reflecting on the book’s deeper themes, Myers said the Dust Bowl context allowed for an authentic exploration of Christian hope.

“To write about hope by writing about the worst ecological disaster in American history is a good way to bring yourself face to face with what hope really means in the Christian sense,” he said. “It is not based on the immediately observable facts of the situation or on our ability to solve things for ourselves. It is not based even on anything being solved in the immediate and usual sense, ‘Though he slay me, I will hope in him’ (Job 13:15). Hope is based on Christ’s promise of redemption for His people and His creation. So, there is no such thing as a situation too bad for hope.”

Myers said he hopes students and young writers everywhere see a message in this national recognition.

“I hope young writers see that you can write seriously as a Christian, that being a Christian writer doesn’t mean glossing over difficulty or tragedy,” he said. “I hope they will see that Christian literature should meet and exceed all the same standards as secular literature. Our first obligation is to steward the talents and opportunities that God has given us and thus to make the best art we can, which means telling all the truth we can. I also hope they see in all art, not just in my writing, that Beauty is an important part of our experience of who God is.”

Ultimately, for Myers, faith is inseparable from his writing vocation.

“I couldn’t even begin to separate my faith in Jesus from my practice as an artist,” he said. “Knowing the story of our sin, fall and redemption in Christ is the only way for me to understand the full context of the particular story I am telling.”

To learn more about OBU’s Division of Language and Literature, go to okbu.edu/language-literature/index.html.

For more about OBU’s honors program, explore okbu.edu/academics/honors/index.html.