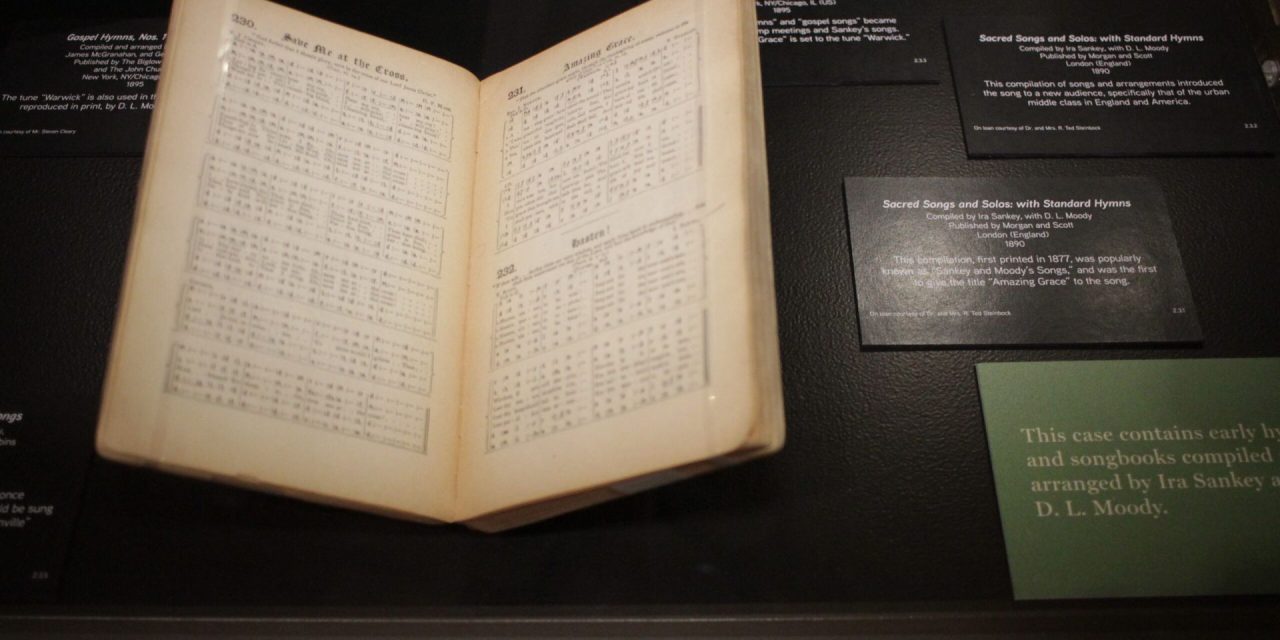

Above: A songbook compiled in 1890 by D.L. Moody and Ira Sankey that includes the song Amazing Grace. (“Museum of the Bible. © Museum of the Bible, 2017)

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (BP) — Folk singer Arlo Guthrie sang it at Woodstock. Pop star Rod Stewart recorded it in 1971. Crowd-surfing is rampant as American Celtic punk rock band Dropkick Murphys perform it on YouTube.

“Amazing Grace,” in its 250th year, has such eclectic appeal and attracts so many genres that ethnomusicologist Paul Benham often discusses with his students whether it’s a gospel song.

“People will sit and argue about it,” said Benham, an adjunct professor of music and ethnomusicology at Liberty University.

Benham and Joshua Waggener, a Southwestern Seminary (SWBTS) professor of church music and worship, both say the song’s pentatonic, or five-note scale common to traditional spirituals, is part of its appeal. The lyrics resonate with many, with certain verses omitted at will.

John Newton: infidel

Amazing Grace was first sung in 1773 on New Year’s Day at Lord Dartmouth’s Great Hall in Olney, England. John Newton wrote it to accompany his New Year’s sermon from 1 Chronicles 17, encouraging worshipers to remember the Lord’s “past mercies and future hopes,” the Museum of the Bible records in an online exhibit.

Such blessings were precious to Newton, a former atheist, exceptionally foul-mouthed sailor and slave trader known for self-proclaimed debauchery. Saved by God’s grace, he ministered 43 years.

Newton claimed conversion in his early 20s when he cried out to God during a violent storm aboard The Greyhound slave ship in 1748 but continued to work in the slave trade for another six years, those latter years as a slave ship captain.

“(Newton) didn’t leave the slave trade immediately following his conversion and never organized the release of any Africans that he had been responsible for enslaving,” the Museum of the Bible quotes journalist and biographer Steve Turner. “Crucially, his captaincy of slave ships didn’t begin until after he had become a Christian.”

Newton’s delayed rejection of the trade has not deterred social justice advocates and Christians alike from embracing the hymn. Those on the right and wrong sides of history have claimed the song as an expression of resilience, determination and protection, including abolitionists and enslavers, the blue and the gray during the Civil War, segregationists and civil rights advocates alike.

Turner notes the irony that the first slaves to sing Amazing Grace would not have known it was the work of someone who actively participated in the cruelty they suffered.

‘Conviction and suffering’

Mahalia Jackson, whose 1947 recording of Amazing Grace is among the most notable, puts the hymn in a category with “The Day is Past and Gone,” a gospel song based on words written in 1792 by Englishman John Leland.

“Those songs come out of conviction and suffering,” Jackson is quoted in the Museum of the Bible exhibit. “The worst voices can get through singing them, ‘cause they’re telling their experiences.”

Benham speaks similarly.

“Everybody’s had toil and trouble, or dangers and toils and snares,” Benham said. “I think that resonates. … It’s almost universal.”

The lack of the name of Jesus in the lyrics also makes the song easier to sing by nonbelievers, said Waggener, who is also SWBTS coordinator of research doctoral programs in church music and worship.

“It is distinctly biblical in its words, distinctly Christian in its origins, but because it doesn’t mention Christ by name,” Waggener said, “it doesn’t use the name ‘Jesus,’ … others can, you might say, appropriate.

“For them, the words ‘grace,’ or even, ‘I was lost,’ or, ‘the Lord has promised good to me,’” Waggener said, “it can mean all kinds of things.”

Both Waggener and Benham note Judy Collins’ 1970 recording of Amazing Grace, an a cappella rendition the Library of Congress preserved in the National Recording Registry as “culturally, historically or artistically significant.” Collins’ recording peaked at 15 on Billboard’s Top 100. It was even more popular in the United Kingdom, spurring the Royal Scots Dragoon Guard, Scotland’s senior regiment, to adapt it for bagpipes.

Collins discussed her faith in a 2007 PBS interview, expressing a blend of Christianity, Buddhism and the Self-Realization Fellowship movement founded by Indian guru Paramahansa Yogananda.

Operatic soprano Jessye Norman sang it at Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday tribute, a rock concert that drew perhaps 70,000 to Wembley Stadium in 1988. Organizers requested the hymn specifically.

“I wasn’t at all sure that was a great idea. And it was certainly something a lot of the rock fans did not understand,” she said of the audience in a 1990 PBS interview with Bill Moyers. “But after a while, they finally quieted down to listen, and some of them sang with me. They were forced to remember why they were there, that it was not only a rock concert; it was a remembrance of somebody that was in prison for the wrong reason.”

Becoming Amazing Grace

The song took decades to reach its current form. It is unknown which music accompanied its first rendition. It was first published in Olney Hymns in 1779 under the title, “Faith’s Review and Expectation,” among a collection of 348 hymns written by Newton and poet William Cowper. As was custom, none of the hymns included musical scores.

American Baptist song leader William Walker was the first to pair it with the tune of “New Britain,” the Museum of the Bible states in its exhibit. It is the most popular soundtrack for the hymn today.

As the song gained popularity across the southern U.S., song leaders would add verses that suited them, expressing contemporary struggles of the day, Waggener said.

“A lot of it has to do with us as Americans. We take something, and we improve on it,” he said. Amazing Grace “took on a life of its own.” The song was particularly fluid in the Black early American Gospel tradition when churches didn’t often use hymnals.

“They could do it how they wanted it,” he said. “A song leader would get up and just say a line, and everybody would sing it. The song leaders had a lot of freedom. They could sing it slow. They could sing it fast. They could add notes. They could subtract notes.

“And once that gets to Mahalia Jackson, she’s sung a lot of hymns, but no one’s sung them quite like that before.”

Among the Library of Congress’ Chasanoff/Elozua Amazing Grace Collection are performances from more than 3000 musicians or ensembles, all available for public listening at the library’s Recorded Sound Reference Center.

Newton had written six verses. The final verse included today was added along the way. It was first printed in 1851 in the abolitionist periodical, “The National Era,” in a 40-week serial telling of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” the Museum of the Bible said.

Waggener sees the last verse as a crucial completion, telling of our heavenly home.

Yet noting the lack of Jesus’ name in the song, Waggener exhorts his students to always include a song that clearly mentions Christ by name when including Amazing Grace in worship.

“So that in that context, it’s clear where our salvation comes from,” Waggener said. “That it is only through the redemption that Christ supplies, and by His grace alone.”